- Home

- Gale, Iain

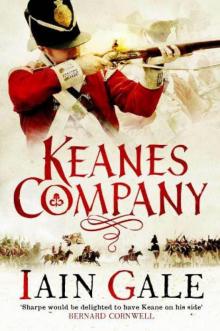

Keane's Company (2013)

Keane's Company (2013) Read online

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Heron Books

An imprint of Quercus

55 Baker Street

7th Floor, South Block

London W1U 8EW

Copyright © 2013 Iain Gale

The moral right of Iain Gale to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HB ISBN 978 1 78087 362 6

TPB ISBN 978 1 78206 091 8

EBOOK ISBN 978 1 78087 363 3

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and events portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures and places, are the product of the author’s imagination.

You can find this and many other great books at:

www.quercusbooks.co.uk

Also by Iain Gale

FOUR DAYS IN JUNE

A novel of Waterloo

Jack Steel series

MAN OF HONOUR

RULWA OF WAR

BROTHERS IN ARMS

Peter Lamb series

BLACK JACKALS

JACKALS’ REVENGE

For Anne and Harry Martin, Keane’s compatriots

PROLOGUE

Morning, and as he took a short step forward with his right foot on the dew-sodden grass, James Keane’s sword caught the early sunlight and gleamed bright and sudden in the dawn. Moving just his right forefinger and his thumb, Keane made the tip of his blade trace a tiny circle in the air around the heart of the man who stood six yards opposite him. The man he had vowed to kill.

They were ready now, but neither man was inclined to make the first move and the razor-sharp edge of Keane’s sword cut the air with a hiss as he took it away from the target and cut down to the left, suggesting a move he might make. As he did so he stared into his opponent’s eyes and smiled. Keane came back en garde and stood, rocking gently on the balls of his feet. Then the referee called to them and at once both men moved towards each other until their blades were close enough to touch.

Keane shivered in his shirtsleeves, knowing that the very slightest movement of the wrist would make the blade move in a sweeping circle and, if he were not careful, open up his guard to a sudden riposte by his opponent.

He caught the other man’s eyes again. Just for an instant. And realized almost too late what was about to happen. The other man, whose name was Simpson, lunged, and Keane, just managing to anticipate him, drew back a fraction to avoid the blade but at the same time extended his own arm so that it flicked up and caught the man on the face, cutting his cheek. The man yelled and stepped back and Keane smiled.

Somewhere he heard the referee speaking: ‘A hit to Mister Keane.’

Keane, fired up now, stepped forward again and by instinct attacked around his opponent’s blade. He knew that Simpson must be hurting now, fighting through the pain, and that he must act fast to capitalize. His blade turned the other and like a flash he was in, the point scoring a hit against the man’s chest. Not deep enough to kill but hard enough to wound.

Again Simpson shrieked and stepped back and Keane recovered. He looked to his left for an instant. Saw his second, Tom Morris, smile at him and realized his mistake as Simpson double-stepped towards him and pushed his blade aside to cut through his shirt and into his chest, cutting open his left breast. Keane sprang back, conscious of the blood now flowing onto his white shirt. Damn, that was not the way he had planned it. He brought his sword up again to the en garde, confusing his opponent and hiding the pain. Both men were tiring now, but Keane had seen the weakness in his enemy. The slightly dropped right shoulder, the trailing blade.

He made ready to strike, but as he did so his mind filled with what had brought him here. An argument over a card game. Idiotic, really. Nothing to speak of.

But he did not regret it. Simpson had been a foolish oaf and to question his honour for a card game was a foolish way to lose one’s life. Of course Keane cheated. Well, didn’t everyone? But the fact was, this time he had not cheated. That was the point. Wasn’t it?

He brought up his sword and again turned it through the air as if to strike to the right, and then, as Simpson brought his own blade across to parry left, Keane aimed for his arm. A flesh wound would suffice now. And then he would offer quarter and the man would accept and honour would be satisfied.

But as he did so Simpson came forward at a rush and before he could stop, the man was hard upon him. But more than that, he had run onto Keane’s blade. Keane felt the cold honed steel sink deep into flesh then grate against bone and then through deeper elements, and he knew that it was done.

He stepped back, pulling his blade as he went, and watched as Simpson’s body slumped to the ground.

Then Morris was at his shoulder.

‘James. James. Quick. We must get away from here. Come. Now.’

And so, in what seemed an eternity, they turned and left as fast as they could go, slipping on the wet grass and making for the light though the clearing, towards the horses and away from the two men crouching over the body of the man who had been Lieutenant Greville Simpson.

1

At a thousand yards the figure of a single soldier appears as no more than a dot shimmering on the horizon; a regiment of men as a solid block of black. As they draw closer, though, it is possible to make out the detail. At six hundred yards you begin to see the individuals who make up the column bearing down on you. By four hundred yards arms become visible, and upright muskets tucked hard against shoulders. But on this fine May morning it was not until they were at two hundred yards that the sun caught the bayonets of the French. Standing in his position in the valley below a small Portuguese town, Keane knew to wait. And wait.

Keane looked at the advancing Frenchmen. A hundred yards. He could see their shakos now with the brass eagle plates and the tall, bobbing yellow plumes of the voltigeurs above blue uniforms and the white cross-belts. And behind them the mass of the column. Drums beating, colours flying, beneath a bronze eagle. He could hear their shouts too, half drowned by the insistent patter of the drums. He spoke again. Calmly, precisely. ‘Take aim.’

One more look as they drew closer. Seventy-five yards. Until he was able, he fancied, to smell the bastards’ garlic breath and look into their eyes before they died. Then, ‘Fire.’

Eighty muzzles flashed into life, fizzing and cracking as hammer fell on flint and flame and smoke spouted from eighty barrels. Keane looked on and watched as the French were hurled back, men falling and jumping, plucked by the musket balls to dance like marionettes. He saw their second rank walk over the bodies of the first, trampling the fallen, dying voltigeurs as they dragged themselves through the dry grass, now stained red.

The commands were given again but they were not needed. Keane’s men knew what to do now. This was their time. The wad was bitten, the ball spat down the barrel and rammed home. Then the carbines were at the shoulders again, and again they cracked out and through the clouds of white smoke that filled the field and choked the throat. He watched more Frenchmen fall, and as he looked on the column stopped. He had known it would. Ten years of war had taught him to expect nothing less of the British soldier. The French were changing now, moving from column into line, desperate to loose off a volley. But it was too late. Keane’s men were already loaded. The third volley in less than a minute crashed out and the French officers died where they stood, even as they shou

ted at their men. And then it was over. Keane saw a colonel topple from his horse and then the bastards were turning. Another volley hit them as they went, and the eagle fell, to be gathered by a fresh pair of hands and hurried to safety in the rear. Keane’s men gave a cheer. One of them, wiping the gunpowder from his mouth, turned to him, smiling. ‘They’re running, sir.’

‘That they are, Thomas, but they’ll come again before the day’s out. Won’t they, sarn’t?’

‘They will, sir, If I know they Frenchies. They’ll be back just as soon as they can.’

Keane smiled. ‘And we’ll see them off again, shan’t we, lads?’

Another cheer, and then a cough from behind him. Keane turned to see the figure of a senior officer, wearing the navy-blue frock coat favoured by many of the staff. He recognized him at once as Major Grant, of the 11th, a man already renowned for his bravery throughout the army, and wondered what business he could have here, in the firing line.

‘Lieutenant Keane?’

‘Sir?’

‘You are relieved of your command. Forthwith.’

Keane looked at him and his heart sank. This was it, then. All that he had been dreading.

‘Sir?’

‘You’re to come with me, Keane, at once. To the commanding general.’

‘To General Hill, sir?”

‘No, Keane, to General Wellesley. He commands now.’

Keane despaired. It was worse than he had thought. He had imagined that General Hill might have got to know that he had taken part in a duel, particularly as it had resulted in the death of his adversary, a brother officer. He did not regret it. Simpson had been a foolish oaf and it had been a stupid way to lose his life. Keane might have been cheating. Well, didn’t everyone sometime? It was just unfortunate that Simpson had moved when he did. Keane had been aiming for his arm but the devil had moved. He wondered what had gone through the man’s mind. Had wondered since it had happened. Whatever the cause, Simpson was dead, and he, it would seem, was in trouble.

He did wonder, though, how the devil Wellesley, newly arrived in Portugal, had come to learn of the matter with such speed, and why had he taken the trouble to take Keane out of the fight in such a manner for such a matter. And to send a staff officer to do it. He could only suppose that he must be used as some sort of example. As a warning from the new commander that, whatever General Craddock and General Hill might tolerate, he would not put up with such behaviour in his army.

Keane cursed himself for his stupidity. To have been called out in a duel and to accept had been expressly against the general’s orders. And what was more, the offence that had provoked the duel – to be found cheating at cards – was almost as bad. Well, to have been accused of it. The conduct of officers was expected to be seen to be exemplary. Even if that were not always the case. Perhaps there was still a chance.

He thought fast. ‘But sir. We are engaged with the enemy.’

‘No, lieutenant, as a matter of fact, you are not. You have just seen them off. Very creditably, as it happens. But that is of no matter. The French are merely bidding us a good morning. They have sallied out from their lines to see what we are about and have been given a sound hiding. Your sergeant is quite able to see them off should they come again. Which they won’t.’

He smiled at the sergeant who nodded, stony-faced, wondering what was going on, and why his officer had been ordered out of the line.

Keane too turned to his sergeant. ‘Don’t worry, Sarn’t McIlroy. I’ll be back soon. Captain Hannan is in command. Take orders from him until I return.’

He turned to catch up with Grant, who, although already a few paces off, had overheard his comment. ‘I’m afraid, Keane, your return may not be for some time. If ever.’

If ever? Keane blanched.

‘Sir, may I enquire as to why I am being summoned by the general?’

‘No, Keane, you may not. You will find out soon enough. Now where’s your mount?’

In the saddle, cantering along the route that would take them back to the headquarters at Coimbra, Keane had more time to think.

All along the allied line the French were pulling back. It had not been a big attack. A brigade at most, sent far in advance against their own to the south of the coastal town of Aveiro. Grant was right. The French were simply trying their strength. Toying with them and seeing that theirs was not an attack in force, they would run back to their lines and let the British do the same. It had been a mistake, Keane knew, for Hill to have pushed forward before Wellesley’s arrival, and what was more it had been, he thought – for all the fact that they had won the day – another example of wasted effort and wasted lives. He hoped that the new general would not make the same mistakes.

And he knew too, to his bitter satisfaction, that whatever his own fate he would not be the only officer to be disciplined that day. Hill had overstepped the mark.

Wellesley had a reputation for caution. The advance into Spain which would surely come would be made slowly and with care. But now it seemed that Keane was destined to take no part in it. He cursed again and dug his boots into the flanks of his horse.

They rode fast and in silence towards the rear of the brigade lines. And all the time Keane felt more apprehensive of what his fate might be.

He had arrived in Lisbon with the battalion in March, a full month ahead of Wellesley, and a high time they had had since then. The city’s jails, it was said, had never been so full, and other buildings had been requisitioned. Sir Arthur Wellesley must surely have wondered at the state of his command. Some, like Keane, had shipped out fresh from home, but other battalions and squadrons had been there since before poor Sir John Moore’s fighting retreat to Corunna last year. You could tell them apart from the new arrivals. Thinner, with their scarlet coats turned to a dirty brick red and their shoes in scraps, they were more inclined to question authority and more often disinclined to obey it.

It was a long ride back to Coimbra, made all the longer by Keane’s trepidation. They stopped after twenty-five miles beside a stream, Grant allowing his horse some water. Keane wondered if now the colonel might give him some inkling as to the truth of his situation, but no sooner had he begun to speak than Grant pre-empted him. ‘Mount up. We must make good time to be there by sunset.’

And so it was as the sun was sinking that at last the town came into view, its great citadel with the Bishop’s palace and the churches rising high above the river Mondego. Almost Wellesley’s first action had been to move the army here. After having divided into three divisional columns, he had marched out of Lisbon and made camp below the town, on the route that must take them from the capital to Soult’s stronghold at Oporto.

As they rode up, the lines came quickly into view. The few proper tents, brought by fortunate officers, stood out amongst the crudely improvised shelters of the men. It was as if a town had sprung up overnight, thronged with thousands of men in coats of scarlet, blue and green and all their hangers-on, who now, even as the muskets blazed, went about their business in the dimming light, moving among the campfires with the focused and mindless purpose of a colony of ants.

The moon shone down from a cloudless sky and the evening was filled with the scent of citrus flowers and lavender, and other, baser smells: woodsmoke, sweat and gunpowder.

Keane brought down his hand heavily against his thigh, swatting a large black fly that had landed on his white breeches, then regretted it, for it had left a bloodstain and the talk in the mess was all that the army commander liked his officers well turned out. Ordinarily it would have worried Keane, but now he was acutely aware of the far greater mess he was in.

It was hard to believe that barely thirty days ago he had been in Cork, waiting to board the ship that would bring him here with 20,000 other men of the army and all their horses and followers.

Since their short halt on the journey Grant had said nothing, had not so much as reined in his horse. Now, as they dismounted and tied up, he was still silent. Keane knew that

it was too late now to ask: all too soon he would discover his fate. As they walked up the final slope of the hill where Wellesley had made his temporary headquarters, Keane wondered what the general would be like. He had not been in Spain the previous year for the debacle that had resulted in Wellesley’s being summoned home in disgrace for allowing the French army to escape. But then the general had won a famous victory at Vimiero and had been cleared by the official enquiry, and now he was back and in command of the army. It was strange, he thought, how such disaster could quickly be followed by triumph. But then, that was war for you. The slightest chance could make a hero of any blackguard and the slightest piece of bad luck reduce the finest of men to a ruined, bloody corpse. And Keane knew that, this time, for once fate had dealt him the poorer hand and it was his turn to suffer.

Wellesley, as was his custom, while having commandeered the Bishop’s palace as his own, had also made a field headquarters beneath the shade of a tree on a rise in the ground that afforded him a good view of the surrounding country. Around its base he had posted a mounted troop from the Blues, and it was to one of their officers that Grant touched his hat as they reached the foot of the small hill. The general was standing with a group of three or four officers around him at a table in the shade of the tree, with a map of the region spread out before him.

Grant approached him. ‘Lieutenant Keane, sir.’

Wellesley said nothing but motioned to one of his staff and whispered something. Grant coughed, quietly. The General did not look up, but nodded sagely and slowly traced a line with his forefinger down the map.

They waited and watched as Wellesley scribbled his signature at the bottom of a sheet of parchment in his notebook, then tore it away and handed it to an aide. Only then did he look up, and when he did so it was straight into Keane’s eyes.

Keane had never met Wellesley before. Yet here at once he knew the nature of the man. The thin beak of a nose, the tight lips set in a lean jaw, and above all, the eyes.

Keane's Company (2013)

Keane's Company (2013)