- Home

- Gale, Iain

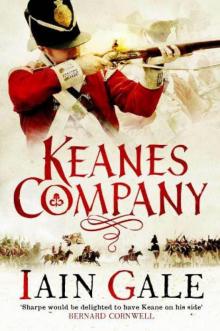

Keane's Company (2013) Page 2

Keane's Company (2013) Read online

Page 2

‘Lieutenant Keane, is it?’

‘Sir.’

‘This is a bad business, Keane. Rotten bad.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘What do you suppose that I should do with you?’

‘I don’t rightly know, sir. Not my place to say, sir. I suppose that I shall be cashiered – at best.’

Wellesley said nothing, but looked down at another piece of paper on his desk. ‘You’re from Ireland.’ He paused, thoughtful for a moment. ‘The Inniskillens. Ten years’ service. Egypt, Alexandria, Malta, Maida.’ He looked up, frowning, ‘Quite a career to date, Keane. Yet you remain a lieutenant?’

‘Yes, sir. I’m afraid so.’

‘And now this. Accused of cheating in the mess and called out by a brother officer and then to have killed him. You know that I have forbidden all duelling.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And that gambling is a vice on which I frown. And moreover to be found a cheat. It’s too bad. There’s nothing else for it. What do you say, Grant?’

‘Yes, sir. I agree. All in all, I’m quite convinced that Lieutenant Keane is the right man for the job, sir.’

Wellesley shook his head. ‘God forgive me, but I’ve been persuaded by Major Grant to give you a reprieve. Against all my better judgement, I’m gazetting you captain. Effective as of now. On my staff.’

Keane was dumbfounded for a moment. Then he found his voice. ‘Thank you, sir. What can I say?’

‘Say nothing. As far as I can see you are a consummate rogue. Do not implicate yourself further or I may change my mind. Say nothing until you hear the real reason that I’ve called you here. I’m looking for someone with particular skills, Keane, and Major Grant here seems to be of the opinion that you might be the man.’

Keane said nothing but wondered what Grant might have seen in him. The general continued. ‘How well do you ride?’

‘Tolerably well, sir. I hunted at home.’

‘Good. That’s something. And you speak French.’

‘I attended the Lycée in Paris as a boy. My mother’s sister was resident there for a while and it was felt that I might benefit—’

‘Any Spanish?’

‘A little, sir. Yes, enough to get by.’

Wellesley nodded. ‘And Grant tells me that you’re considered something of an artist in the mess. Is he right?’

Keane smiled. ‘He is kind, sir. I like to think that I can capture a likeness. Nothing more.’

‘Can you capture the likeness of a place?’

Keane nodded, ‘Yes, sir. I do draw landscapes. And any buildings that take my fancy. In fact I’ve just completed a drawing of—’

Wellesley smiled to silence him. ‘Fine, that’ll do. You are a good shot?’

‘Since my youth, sir. I shot partridge at home on the farm.’

‘And Frenchmen these last ten years. And you’re fit? I can see by the look of you that there’s little flesh on you.’

It was true, thought Keane, he was in good condition. He had never been unfit and ten years’ soldiering had ensured that his body was nothing more than muscle, sinew and bone.

‘I was brought up in Ireland by my mother, sir. My father being dead, I had to do his work on our farm. And that of others.’

Wellesley stared at him. ‘And my sources tell me that you have a way with words too, Keane. That you are able to talk your way out of any situation.’

‘I do hope so, sir.’ He paused. ‘Not this one, though.’

‘No, not this one. No amount of lie and bluff will help you now. Were you cheating at cards, Keane?’

‘On my honour, no, sir. Lieutenant Simpson was mistaken. It was he who slighted me and on my being challenged, sir, I had no alternative but to accept.’

‘You are aware that Lieutenant Blackwood stands by the word of Lieutenant Simpson, who is, of course, no longer able to speak in his own defence.’

‘I protest at Lieutenant Blackwood, sir. It was I who was insulted.’

‘That was not what I asked you. Nor did I ask you to implicate Lieutenant Blackwood, whose father I have known since we were boys. I asked whether or not you were a cheat. But as it is universally accepted that you are a liar, then I imagine we shall never know the truth. You are a convincing liar, though, Keane. That much I can see to be true.’

He looked at Grant.

‘It seems, Colquhoun, that you may indeed have been right.’ He turned back. ‘Welcome to the staff, Captain Keane.’

Keane smiled and bowed. ‘Thank you, sir.’

‘And now I am dismissing you from it.’

‘Sir?’

‘You heard me aright. From now on, Keane, you will be my eyes and ears. You will report to me or to Major Grant here, directly. You will also take orders when appropriate from Captain Scovell.’

As if on cue, like an actor in the wings another officer, who had been standing silently behind Wellesley, made his way forward and smiled at Keane. He was younger than Grant and less weather-beaten.

Wellesley went on, ‘Captain Scovell here will be in command of several units similar to your own, yet not all of them, it would seem, will be possessed of your particular capabilities or qualifications.’ He smiled at Grant and then looked back to Keane. ‘We face an enemy of whom we must have the measure, or we shall fail. Marshal Soult is at Oporto with some twenty thousand men. Marshal Ney is in Galicia and Marshal Victor at Merida with yet more again.

‘I need to know everything. Everything, Keane. I want you to get yourself behind the French lines and find out anything you can. Draw pictures of any fortifications, or indeed any buildings which might be of use to us. I want their plans, their troop numbers, ammunition stocks, morale. What the commander had for breakfast. And I don’t care how you do it. And if in the course of your work you have any opportunity to disrupt their operations and delay or forestall them, then do it. Oh, and you shan’t be going alone. You’ll have a platoon. A troop, if you will. A company, perhaps. You are at liberty to choose who you will from the ordinary soldiers of the army.’

‘From all regiments, sir?’

‘All regiments and all arms, Keane. Infantry, cavalry, artillery. The choice is yours. But if you want my advice, don’t look too high. Cutthroats, murderers, thieves: take your pick, the army’s full of rogues. I dare say you’ll understand them all very well. One in fifty of our brave fellows comes to the colours to escape the law. Major Grant? I’m finished with Captain Keane. Good day and good luck, captain.’

Keane gave a bow and, turning, walked away, feeling both elated and terrified. ‘Captain Keane.’ Grant was hard behind him. ‘A word, Keane.’

‘Sir?’

‘This is a rum do. But the general has it in his head, so it can’t be helped. If you want my opinion you’ve less chance than a man on the gallows. But get the right men behind you and you’ve more likelihood of not being killed quite so soon. You’d best start with the Lisbon jails. And you’ll need to choose carefully.’ He laughed.

‘You’ll need men with a variety of skills. A picklock would be useful to you, and a thief who can climb. At least one of them would have to be fluent in Spanish and another in French. They might need to look swarthy to pass for either. You might need a forger, and they’ll all need to ride. We’ll supply your mounts, and do try not to wear out the poor beasts, or lose them. Even though they’re sure to be useless nags, all of them. We do not have a limitless purse for your activities, vital as they are.’

‘You mean that I should recruit from the jails, sir?’

‘I’m in deadly earnest. We’ve three of them full in Lisbon already and others filling up. Damned smart work by the provosts. Though I dare say they had their hands full. Filthy place. All drink and bad women. You won’t be lacking in material. Take your officer though from where you will. You’ll need an officer with you, Keane. To keep you sane.’

‘What uniform do we wear, sir?’

‘Well, only you can decide on that. If you want to avoid dete

ction, of course, you should perhaps not wear any. But remember that if that is the case and you are caught you will be shot or hanged on the spot for a spy. I would advise that you keep some article of uniform somewhere about you for that purpose. You and all your men. I prefer to travel in full uniform, myself.’

‘You go behind the lines, sir?’

This was something new to Keane. Scouting patrols he was aware of, and the fact that some officers had been selected to gather information on the enemy. A job that few would have wished for. But an officer attached to the staff riding into enemy territory to gather information? He had never heard the like.

‘Frequently. It’s most exhilarating. I know you’ll rise to it, Keane. Best life in the world for a soldier. Whatever anyone may say. And now you had better go and find your colonel and tell him your good news. I dare say he’ll be upset at losing you, Keane. You may direct him to me should he need to be convinced. See you in Spain, my boy. And you had better find yourself a billet for the night. You’ve a long journey ahead of you back to Lisbon. I would suggest you put into a mess. Try the artillery.’

*

Leaving Grant behind, Keane walked slowly back through the lines in search of a billet.

His head was still reeling from all that had happened. He had gone to the general expecting to be drummed out of the army and had been rewarded instead with sudden promotion. And then this. He was not sure what to make of it. Certainly it was better than being cashiered and disgraced or court-martialled for murder. And it was promotion, but to what must surely be one of the most detested jobs in the army. He supposed that he ought to be thankful for it, but he knew in his heart that his job was to remain in the firing line with his men. But it was, as Wellesley had said, a position that might have been made for him.

Keane knew that he could lie. And lie damn well. He’d become good at it while still a boy. In Ireland, when circumstances had reduced his family to penury and he had been forced to steal his neighbours’ sheep to make ends meet. In truth his letter of commission – a complete surprise – had come, he thought, in the nick of time. It had been paid for by an anonymous friend of whose identity he remained unaware, and although his mother had begged him not to take it, not wanting to lose her son, Keane could not help but go. And so in the autumn of ’98 he had become a soldier.

He had spent the last ten years as a company officer, learning to drill men in line and column. Teaching them to stand as he did and take the shot and the musket volleys before they loosed their own and sent the French to hell. Ten years of it. He thought back on the men he had known and lost. On the wounds and the times he had cheated death.

Well, he would do Wellesley’s dirty work, and do it well. Providence had rewarded him in kind and now he knew he must make the most of this chance he had been given. And he knew too that, when the opportunity arose to rejoin his battalion, he would be sure to take it. The true glory of any war lay on the battlefield and Keane had made a promise to himself that if any glory and honour were to come out of this war, then he would surely have his share. That and whatever worldly riches he could take by any means. He was no common thief. But if any chance of booty presented itself, then Keane knew that he would take it. And one day, when all this was finished, he would return to County Down a rich man and damn those who had cursed him for a wastrel.

And he would keep his uniform, as Grant had advised, with its canary-yellow facings and with the castle of its home town on its brass buttons. Even with his stained breeches. He wondered when he would be able to pay for them to be cleaned. From his daily pay of five shillings and threepence it would mean a sixpenny deduction, and that, after all other mess expenses, would leave him in lack of funds. Such was the lot of an impecunious officer. His new rank of captain would certainly double his pay. But when, he wondered, would he see any of that? They all knew that one of Wellesley’s problems was with the payroll.

He would keep too the curved sword of the light company, his company, that clanked and rattled at his side. The ivory-hilted sword he had been given after the battle of Maida by a grateful commander and which had seen him through ever since, sending many a Frenchman to meet his maker.

What really angered him was that he knew he would miss his men. In particular his sergeant, George McIlroy, with whom he had been through so many close calls and who had taught him much of all he knew about soldiering. It had been McIlroy too who had thrust his bayonet high as the battalion had stood against the French dragoons on the beaches of Flanders nine years ago, parrying the sabre slash that would have ended Keane’s young life.

With the French sent scuttling back to their own lines, the army was preparing to move. Wellesley intended to flush them out from the town and now that he had seen their strength, Keane knew, he would not delay.

In the meantime, those men who knew that at any time now they would be in the thick of the line of battle were doing their best to complete their tasks before the order came to move. While some shaved, others fed on stirabout or simply gathered up their meagre effects. Women, wives – common-law and otherwise – sat with their infants while other children ran about playing among the piled muskets. One of the women, up to her elbows in water at a tub, called to him as he passed: ‘Hello, ducky. Need yer breeks washed? Take ’em off and give ’em here.’

Ignoring her, he walked on and with a heavy heart went in search of friends and a good bottle of wine.

*

The streets of Coimbra were not unlike those of Lisbon. Beautiful yet vile. Most of the townspeople had retired inside for the night, although here and there at the cafes men sat playing dice and backgammon. While the rank and file had been confined to the camp down in the valley, the better class of British officers had, as was their custom, chosen to make their temporary homes in the houses of the town. He had been told by Grant that the finer houses were on the upper part of the hill and so he climbed now in search of a mess that might offer him some hospitality. The artillery had been a good suggestion. He had never found their hospitality wanting and there was even a chance that an old friend might be here.

At length, close to eight o’clock, at the end of a cobbled street near to the palace, he found a merchant’s house, simple and with a single balcony. Outside, an artilleryman armed with a musket stood guard. Keen nodded to him and entered, hoping for a welcome.

What he found was beyond anything he could have wished for.

For there, sitting on a chair in the entrance hall outside the mess room proper, he found the man whom he could call his oldest friend in the army. Wanting for money like himself and thus still a lowly lieutenant, Tom Morris of the Royal Horse Artillery was nevertheless a legend on the battlefield. The man who had killed twelve French alone at Alexandria and who at Maida had single-handedly rallied the 78th. At present, though, he was content to be sitting outside the mess sipping a glass of madeira and playing with his dog, a terrier named Hercules.

Seeing Keane, he leaped from his chair. ‘James? What news? They say you were called to see Wellesley?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well then, what news? Why did he ask for you? They say you’re appointed to the staff.’

Keane nodded. ‘Yes, that’s right. And removed from it.’

‘Removed? How “removed”? How’s that?’

‘I’m to be given a command.’

‘James, what luck! What are you to have? A company? Is it with the 27th? Not the Devil’s Own, the 88th?’

Keane shook his head.

‘With whom, then? It is promotion?’

‘Yes, I am to be promoted captain.’ He paused. ‘I’m to be an exploring officer.’

Morris frowned. ‘Oh. I see. How then can you have a command?’

‘I’m to have a platoon. Or rather, a troop. We are to be mounted. We operate behind the enemy.’

Morris shook his head. ‘I am sorry for you, old friend. That’s not real soldiering.’

‘Yes, I know. I had wondered whether I might still

be welcome in any mess, or indeed quite to what part of our military family I now belong.’

‘Don’t talk such rot, James. Did Wellesley know of the duel? And Simpson?’

‘Oh yes. He gave me no respite on that count. D’you know Blackwood’s father is an old friend of his?’

‘I say, that’s bad luck. But he still promoted you.’

‘Yes. I’m still attempting to fathom it out. It is not what I would have wished, Tom, but it is what I must do, it seems, if I am to survive in this army. I thought I would be cashiered, on account of Simpson’s death. But this. Promotion, for God’s sake. With a captaincy.’ He laughed. ‘Now you must call me ‘sir’. Come on, let’s celebrate. But no fuss.’

Together they entered the mess, which contained a dozen officers. Finding a soldier-servant, Keane managed to get a bottle of the local wine left behind by the French. Morris walked across to one of the drums, which had been laid in the mess as was the custom, and before Keane could stop him was thumping on it with his fist, silencing the room.

‘Lieutenant Keane has expressed his desire to buy a drink for every officer present on the occasion of his captaincy.’

There was chorus of hurrahs. Several of the officers, two from his own regiment, clapped him on the back. Another, though, in the dark-blue uniform of an officer of the Light Dragoons, approached him more slowly.

‘Well done, Keane. Well, well. This is a surprise. When I heard you had been called for, I presumed the worst: that the commander meant to ask for your sword.’

‘No, Blackwood. I’m promoted. I didn’t expect your congratulations.’

‘Sorry, did I offer them? My mistake. Tell me, Keane, to what regiment you might be gazetted captain? The Guards?’

‘No. As a matter of fact, I am to be close to the general. An exploring officer.’

Blackwood laughed and repeated the words, slowly. ‘Exploring officer. Well, that’s better than I could have wished. Of course I expected nothing more from you, Keane. It seems fitting that you should end up playing the spy. It is not a gentleman’s work. But then you are not—’

Morris spoke. ‘I’ll thank you to hold your tongue, Blackwood.’

Keane's Company (2013)

Keane's Company (2013)